You have to look at white whiskey

on its own merits.

If you judge it

compared to aged whiskeys,

it fails.

Every time.

~ Darek Bell

Corsair Artisan Distillery

|

| Shea Shawnson pours Double and Twisted light whiskey at Elixir |

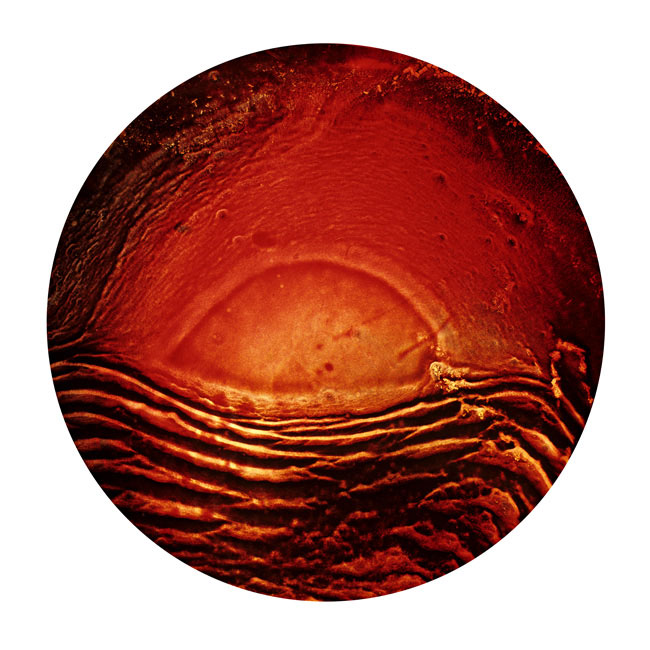

As grain spirits come off the still, in- dustry insiders call the heady, limpid distillate new make or white dog. Every whiskey distiller in the world makes it and almost all of it is destined for barrels. Some, though, trickles out to the public. Lately, distillers and consumers alike have taken to calling it white whiskey. Marketers trumpet it as a hot new thing. In truth, the wheel has been around longer. And fire, of course. But new make was old hat when Johnnie Walker took his first wobbly steps.

What is novel is that until about 2005, few dreamt a market still existed for the stuff.My travels brought me up the west coast of the United States. From tiny sheds up dirt roads to a distillery in an old Air Force hangar, I met with men and women making, selling, drinking, and mixing white whiskeys.

Bars and restaurants from New York to Seattle offer white whiskeys as a matter of course, even pride. White Manhattans and albino Old Fashioneds abound. If whiskey cocktails unblemished by oak are insufficiently exotic, trendy tipplers can ask for them “improved” 19th-century style with a few dashes of absinthe.

Despite growing awareness and acceptance, the category is dogged by three recurrent questions. Two are worth addressing in passing: (1) Is white whiskey moonshine? and (2) Is it any good?I tackle those in about 500 words, but the third question, the one people should be asking and which fills the bulk of the article, is what do we do with it? Pick up the Winter 2012 issue of Whisky Advocate for some of the answers — including arguments that the way many white whiskeys are made is completely wrong — or download a PDF of It's a Nice Day for a White Whiskey here.

Interviews, insight, and recipes from Thad Vogler of Bar Agricole and Shea Swanson of Elixir in San Francisco, Darek Bell of Corsair Artisan Distillery (and author of Alt Whiskeys), Jim Romdall of Vessel in Seattle, Ian and Devin Cain of American Craft Whiskey distillery, barber and distiller Salvatore Cimino, 13th generation master distiller Marko Karakasevic from Charbay, and, midwife to the modern tiki renaissance, Jeff "Beach Bum" Berry.

Here's a bonus recipe that didn't make the article from bartender Rhachel Shaw whom I ran into as a customer at rum bar Smuggler's Cove. Shaw pays tribute to Elizabeth Taylor (whom one can only presume guzzled staggering quantities of raw whiskey) with a drink named for the late movie star's perfume:

White Diamonds

1.5 oz. Koval Chicago Rye

.75 oz. Cocci Americano

.5 oz. Maraschino

1 dash Bitterman's Grapefruit Bitters

Stir on ice. Strain. Garnish with grapefruit peel.