The archives of a sporadic discussion about drinks, food, and the making thereof

Friday, June 29, 2012

Iron and Blood

In the wake of the Supreme Court's decision on so-called "Obamacare" and its implications for future interpretation of the commerce clause of the US Constitution, let us take comfort in, and never forget the sage words of, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Two Lemonades: Fresh or with a Soulless Ginger Twist

Summer has come on cruelly for parts of the United States. Since last week, temperature spikes in the Midwest and East Coast have made me worried for family...and relieved that San Diego remains, as ever, lovely.

I will be traveling to those hot and humid places over the next few weeks, though, and undoubtedly will keep cool with beer, whiskey, iced tea...and lemonade.

I don't bother with pre-made lemonade, the powders and mixes. I'm not all snooty and think they're too sweet or otherwise unhealthy — it's just that fresh lemonade is easy to make from three ingredients we always have on hand; lemon juice, water, and sugar syrup. Why fake it when doing it properly takes so little effort?

This is an extremely versatile basic recipe. The ratio of ingredients is a straightforward 5:5:3, so use cups, milliliters, coffee mugs, etc. Any volume will work as long as you maintain the ratio. Scale up or down as your thirst, crowd, and container size dictate.

I strained the ginger water and set aside 250ml. About about 350ml remained, so I added twice the volume of sugar (700ml) and heated the mix in a pot just enough to dissolve the sugar. With everything in place, it was simple to make a batch of

Goes well with:

I will be traveling to those hot and humid places over the next few weeks, though, and undoubtedly will keep cool with beer, whiskey, iced tea...and lemonade.

I don't bother with pre-made lemonade, the powders and mixes. I'm not all snooty and think they're too sweet or otherwise unhealthy — it's just that fresh lemonade is easy to make from three ingredients we always have on hand; lemon juice, water, and sugar syrup. Why fake it when doing it properly takes so little effort?

This is an extremely versatile basic recipe. The ratio of ingredients is a straightforward 5:5:3, so use cups, milliliters, coffee mugs, etc. Any volume will work as long as you maintain the ratio. Scale up or down as your thirst, crowd, and container size dictate.

Fresh LemonadeMonday, I was faced with a pot of ginger-infused water. It was leftover from Sunday night's ginger tea. Rather than throw it out, I swapped it out for the water I would otherwise use in the above recipe and made ginger syrup with the rest.

17oz/500ml fresh lemon juice

17oz/500ml cool water

10oz/300ml 2:1 sugar syrup

Mix in a pitcher. Chill if you've got time. Pour into glasses over fresh ice.

I strained the ginger water and set aside 250ml. About about 350ml remained, so I added twice the volume of sugar (700ml) and heated the mix in a pot just enough to dissolve the sugar. With everything in place, it was simple to make a batch of

Soulless Ginger LemonadeOf course, if you have ginger syrup on hand already, this is a snap to make. Just use that and plain cool water. Doctor this any way you see fit; blend it with blackberries, spike it with mint or basil, but don't forget the ameliorative effect a stiff dose of bourbon could have on a glass of ginger lemonade. Carbonate the stuff, add a dash of bitters with the bourbon and you've got something pretty close to a Kentucky Mule.

Soulless? Does it lack the pungency and bite we expect from fresh ginger? No, that's there. It's even more refreshing than the plain version. Soulless because, as even we gingers know, we have no souls.

8oz/250ml fresh lemon juice

8oz/250ml cool ginger-infused water

5oz/150ml 2:1 ginger syrup

Mix in a pitcher. Chill if you've got time. Pour into glasses over fresh ice.

Goes well with:

- Empinken your drinkin' with pink lemonade — a look at its history and notes on execution (hint: use cocktail bitters).

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

There is Nothing in the World More Helpless

In the course of researching American moonshine and Irish poitin, I have naturally come across many references to ether use, abuse, frolics, and binges. This is in the running for my favorite quote of all.

Monday, June 25, 2012

Ginger Tea After Shouting at the Pipes

Sunday nights, I often meet friends out for beers and tequila. Not last night.

Last night, as my friends gamely tried to have as enjoyable a time as they could manage without me (this is how I imagine it goes when I'm not around), I was curled on my bathroom floor, sweating, shivering, too weak even to reach for the phone. "Come," I wanted to plead. "Bring me water." I had an inexplicable, insatiable craving for butterscotch candies. My febrile hallucinations were occasionally interrupted with bouts of roaring at the porcelain. Afterwards, the cool tile floor felt so, so good.

When Dr. Morpheus came home hours later, the verdict was swift: food poisoning.

Though we didn't have butterscotch candies, I got water and, after a while, ginger tea. We call the stuff ginger tea, but the hot drink is more properly a decoction. That is, it's a highly seasoned liquid that's been flavored by long, low cooking of plant matter in water. See? It's kinda like tea. Calling it a decoction around the house, though, is like calling a possum an opossum; technically correct, but a bit contrived.

Ginger has long been regarded as soothing to upset stomachs. You may recognize it from that ginger pie I sometimes bake. I break out this decoc...this tea now and then to combat queasiness. Even if the effect is a placebo, sipping this hot, bracing tea helps me feel just a little better. But I tell you this: when I'm wrapped in a towel to ward off chills and my clammy, sweaty head is pressed against the cool toilet like it's dispensing God's own heavenly grace, a little better makes a world of difference.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I still feel wrecked, like I've been mauled by a cougar or fell off a speeding truck. I'm off for some Ibuprofen and tea.

Last night, as my friends gamely tried to have as enjoyable a time as they could manage without me (this is how I imagine it goes when I'm not around), I was curled on my bathroom floor, sweating, shivering, too weak even to reach for the phone. "Come," I wanted to plead. "Bring me water." I had an inexplicable, insatiable craving for butterscotch candies. My febrile hallucinations were occasionally interrupted with bouts of roaring at the porcelain. Afterwards, the cool tile floor felt so, so good.

When Dr. Morpheus came home hours later, the verdict was swift: food poisoning.

Though we didn't have butterscotch candies, I got water and, after a while, ginger tea. We call the stuff ginger tea, but the hot drink is more properly a decoction. That is, it's a highly seasoned liquid that's been flavored by long, low cooking of plant matter in water. See? It's kinda like tea. Calling it a decoction around the house, though, is like calling a possum an opossum; technically correct, but a bit contrived.

Ginger has long been regarded as soothing to upset stomachs. You may recognize it from that ginger pie I sometimes bake. I break out this decoc...this tea now and then to combat queasiness. Even if the effect is a placebo, sipping this hot, bracing tea helps me feel just a little better. But I tell you this: when I'm wrapped in a towel to ward off chills and my clammy, sweaty head is pressed against the cool toilet like it's dispensing God's own heavenly grace, a little better makes a world of difference.

Ginger Tea for an Upset Stomach

The proportions here are to taste, but the end result should smell and taste strongly of ginger. I like a bit of honey to round out taste and to soothe my throat, but leave it out if you got some beef against honey.

1 quart/liter of water (more or less)

8 oz/ 230g fresh ginger

Honey (optional)

Wash but do not peel the ginger. Slice into fat coins or ovals. Put them in a nonreactive pot big enough to hold around 1.5 quarts. Pour the water over it. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for about 20 minutes. Strain some into a glass or mug, sweeten with honey to taste, and return the pot to a low flame.

Top off with fresh water now and then as you strain off more to drink until the ginger loses its potency or you just get sick of the stuff.I haven't tried this next bit, but it stands to reason that when you're done with the drink and there's some left in the pot, you could strain off the solids and add twice the volume of sugar as tan ginger water is left. Heat just until the sugar dissolves and you've got yourself a nice ginger syrup for cocktails or drenching cakes or whatever.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I still feel wrecked, like I've been mauled by a cougar or fell off a speeding truck. I'm off for some Ibuprofen and tea.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Amsterdamse Krulletter, a Script from Amsterdam's Brown Cafes

It's no revelation that I like booze. Sooner or later with new acquaintances, I pin Amsterdam as one of my favorite places in the world. But a quirk kept a little tighter to my chest is that I'm a complete typography and font geek.

Oh, I'll spend hours after I should have gone to bed, staying up staring at the glowing screen until tears of fatigue flow freely down my cheeks. I grew up in a house with not only a butter churn, but also printers' drawers; early exposure to block lettering instilled an abiding interest in minding p's and q's. More than once, as I've trawled through the offerings of online font vendors, trying out phrases, and learning how various designers have used this or that font, dawn has taken me by surprise.

Ramiro Espinoza has combined all three elements — booze, Amsterdam, and fonts — in one tale. Espinoza lives in Amsterdam where he runs the digital font foundry, Re-Type. Intrigued by the cursive, curly script he found on the city's "brown cafes" (i.e., neighborhood pubs) and concerned that they were disappearing as old facades succumbed to renovations and new owners, he set about tracking down why the pubs in particular used this distinctive hand-painted font.

Read his ILoveTypography.com article and check out additional photos here.

Read his ILoveTypography.com article and check out additional photos here.

Edit:Thanks to Jacob Grier for reminding me that the ancient Dutch distiller Bols uses some now-familiar lettering on its genever bottles. It is used again here (right) on the 2011 release of its barrel-aged genever. The regular version comes in a smoked-glass bottle while the barrel-aged genever is sold in tall but hefty traditional stone jugs. It's a nice nod to Amsterdam's drinking history.

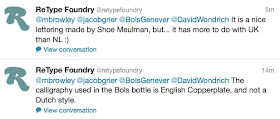

Feh. Mistakes when I'm alone are bad enough, but making them here in this public forum is deeply embarrassing. The why of it doesn't matter, but I posted copy without checking facts. Sorry about that. Good news, though: we've heard from ReType Foundry more about the Bols script. Seems we should be looking toward England rather than the Netherlands for this one:

A note on pronunciation: Americans tend to pronounce this malt-wine spirit "GEN-uh-ver" but every Dutchmen I know calls it "ye-NAY-ver." On his show The Layover, Anthony Bourdain either plays it safe or forgets; he uses both.

I'm going with the cloggies on this one. Grab yourself a bottle or two. Good stuff to hand on hand.

Oh, I'll spend hours after I should have gone to bed, staying up staring at the glowing screen until tears of fatigue flow freely down my cheeks. I grew up in a house with not only a butter churn, but also printers' drawers; early exposure to block lettering instilled an abiding interest in minding p's and q's. More than once, as I've trawled through the offerings of online font vendors, trying out phrases, and learning how various designers have used this or that font, dawn has taken me by surprise.

Ramiro Espinoza has combined all three elements — booze, Amsterdam, and fonts — in one tale. Espinoza lives in Amsterdam where he runs the digital font foundry, Re-Type. Intrigued by the cursive, curly script he found on the city's "brown cafes" (i.e., neighborhood pubs) and concerned that they were disappearing as old facades succumbed to renovations and new owners, he set about tracking down why the pubs in particular used this distinctive hand-painted font.

In a way, my research into the ‘Amsterdamse Krulletter’ (Amsterdam’s Curly Letter) began eight years ago as I was walking down the streets of what is possibly the city’s most beautiful district, the Jordaan. As every local knows, this area hosts quite a few of the old, traditional pubs that the locals call ‘bruin cafés’ (brown cafés). In urban environments, type designers are always looking at letters, and especially at hand-painted ones. It didn’t take me very long to notice that many of the pubs in the area had their windows painted in a very interesting and beautifully executed script. Later I discovered they had been painted throughout other parts of Amsterdam too, notably also in the De Pijp area.Espinoza tracks some of the examples to Leo Beukeboom who began painting for Heineken Brewery in 1967 and who hand-lettered signs for pubs sponsored by Heineken. "But," he writes, "the history of the style goes back further than that." Espinoza lays out his detective work on this beery lettering with additional connections to Amstel Brewery and 17th century Dutch calligraphy.

Read his ILoveTypography.com article and check out additional photos here.

Read his ILoveTypography.com article and check out additional photos here.Edit:

Feh. Mistakes when I'm alone are bad enough, but making them here in this public forum is deeply embarrassing. The why of it doesn't matter, but I posted copy without checking facts. Sorry about that. Good news, though: we've heard from ReType Foundry more about the Bols script. Seems we should be looking toward England rather than the Netherlands for this one:

A note on pronunciation: Americans tend to pronounce this malt-wine spirit "GEN-uh-ver" but every Dutchmen I know calls it "ye-NAY-ver." On his show The Layover, Anthony Bourdain either plays it safe or forgets; he uses both.

I'm going with the cloggies on this one. Grab yourself a bottle or two. Good stuff to hand on hand.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

Make-Believe Moonshine in Massachusetts

Regular readers know that I take a dim view of calling "moonshine" all those clear grain- and sugar-based spirits cropping up from American distilleries. Doing so obscures the fact that moonshine was — and continues to be — made from nearly every carbohydrate available in North America from persimmons and pumpkins to quinoa and triticale. Sometimes, it is aged for decades. It was always illegal. Always. This so-called "legal" moonshine is a recent historical fallacy, one promulgated by marketers and distillers in the last five or six years who hope you'll suspend disbelief long enough to buy a bottle or jar.

That's not to say I don't like some of these make-believe moonshines. Some are quite good and modern bartenders have been making exceptional cocktails with them. Shoot, friends of mine — welcome guests at my home — make the stuff. I'm just not moved by attempts to redfine a word that has, for three centuries, entailed illicit distillation.

If I were anywhere near Julio's Liquors in Westborough, Massachusetts this weekend, though, you can bet that I'd be front row at the Loch &K(e)y Society's MASS Shine 2012 Expo and Competition (on Twitter as @MassShine). Alas, I'll be under three deadlines three thousand miles away. Distiller Curtis McMillan will present "Understanding taxed moonshine" (ahem) and Gable Erenzo of Tuthilltown Spirits will be talking about New York state moonshine.

For details on times which distillers will be on hand to share their wares, and how to sign up for the free classes, head over to Julio's website.

Do go if you're nearby. Do meet the distillers. Do try their spirits. Just...take as many grains of salt as will fit in your pocket.

Goes well with:

That's not to say I don't like some of these make-believe moonshines. Some are quite good and modern bartenders have been making exceptional cocktails with them. Shoot, friends of mine — welcome guests at my home — make the stuff. I'm just not moved by attempts to redfine a word that has, for three centuries, entailed illicit distillation.

If I were anywhere near Julio's Liquors in Westborough, Massachusetts this weekend, though, you can bet that I'd be front row at the Loch &K(e)y Society's MASS Shine 2012 Expo and Competition (on Twitter as @MassShine). Alas, I'll be under three deadlines three thousand miles away. Distiller Curtis McMillan will present "Understanding taxed moonshine" (ahem) and Gable Erenzo of Tuthilltown Spirits will be talking about New York state moonshine.

For details on times which distillers will be on hand to share their wares, and how to sign up for the free classes, head over to Julio's website.

Do go if you're nearby. Do meet the distillers. Do try their spirits. Just...take as many grains of salt as will fit in your pocket.

Goes well with:

- Legal Moonshine? You've Been Conned

- Even the Ten Dollar Whore Sneered at Me, a look at how far white whiskeys have come in a few short years.

- Lots of moonshine (actual moonshine) flowed during Prohibition. Here's a look at a 1927 recipe calling for Georgia or Maryland "corn."

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

A Dispiriting Glimpse at Molecular Mixology's Latest Offering

My book Moonshine has lots of sidebars, little snippets of text related to the nearby sections, but just enough off-topic that they felt clunky in the main copy. They reflect my scattershot, parenthetical way of thinking and the somewhat difficult time I have keeping my tongue in check. One such sidebar I cut from the final draft concerned booty bumps.

Booty what? Oh, come now. Don't tell me you've never heard of booty bumps.

Working from the delusion that those around them are unable to detect its aroma, certain day drinkers drink only vodka. Regardless of federal guidelines that specify vodka is to be odorless and tasteless, it is neither. In fact, vodka has a distinct odor and only seems odorless and tasteless when compared with whiskeys, rums, brandies, and other spirits that have more obvious characteristic smells. In other words, we're all onto you, drunkie.

Consumers who want to employ an even sneakier workaround, several informants explained, may take their alcohol from the other end. They may, in effect, take vodka enemas. Ethanol is absorbed rapidly into the bloodstream through the membrane of the lower intestine, delivering the alcoholic punch of a shot of booze, but without the resultant telltale vodka breath. The booty bump. Of course, it's easy to take poisonous amounts of alcohol into one's system accidentally through this inelegant backdoor method. Lest there's any uncertainty; it is not advised.

The things one learns in the course of pursuing a life in alcohol.

I was reminded of this alternate quick-delivery system because this Sunday's Guardian featured a story about the WA/HH spray that's just gone on sale in Paris. Kim Willsher writes:

If molecular mixology continues in this direction, that ass full of vodka might not seem like such a bad idea.

Booty what? Oh, come now. Don't tell me you've never heard of booty bumps.

|

| Photograph: Franck Fife/AFP/Getty Images from The Guardian |

Consumers who want to employ an even sneakier workaround, several informants explained, may take their alcohol from the other end. They may, in effect, take vodka enemas. Ethanol is absorbed rapidly into the bloodstream through the membrane of the lower intestine, delivering the alcoholic punch of a shot of booze, but without the resultant telltale vodka breath. The booty bump. Of course, it's easy to take poisonous amounts of alcohol into one's system accidentally through this inelegant backdoor method. Lest there's any uncertainty; it is not advised.

The things one learns in the course of pursuing a life in alcohol.

I was reminded of this alternate quick-delivery system because this Sunday's Guardian featured a story about the WA/HH spray that's just gone on sale in Paris. Kim Willsher writes:

With one squirt, its inventors promise, you'll feel all the euphoria of being inebriated for a few seconds without the nasty side-effects of behaving like an idiot and falling over.Willsher goes on:

With each squirt from the WA/HH spray delivering just 0.0075ml of alcohol and about 20 squirts in each €20 (£16) lipstick-sized spray, it's pricey night out – the equivalent of €1,300 (£1,000) for a unit of alcohol.What's next? Whiskey tabs that dissolve on one's tongue? Patches that deliver small but continuous doses of Cognac for hours on end? Call me old fashioned, but I like my whiskey, wine, cider, port, rum, punch and other boozy repasts down my throat in liquid form. Ok, and maybe occasionally as a jelly. I enjoy the taste of alcoholic drinks. God help us all if we grow old in a world where the best option for a stiff drink is £1,000 spritzes of aerosol grain spirits.

If molecular mixology continues in this direction, that ass full of vodka might not seem like such a bad idea.

Sunday, June 10, 2012

Getting the Apple out of Apple Whiskey, 19th Century-Style

Among the papers of John Ewing held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania lies an undated manuscript from about 1810. It describes a process for making a variety of ersatz liquors from a base of apple brandy, often called in early American idiom, apple “whiskey.” Once treated with charcoal and redistilled, such local orchard brandy could be made to seem like French brandy, Jamaican rum, Holland gin, etc. Emulating more expensive imported liquors using local goods was common throughout the colonial era, through the early Republic, and into the twentieth century. Time and time again, I come across recipes for faking one kind of spirit with another in household account books and recipe manuscripts. Though it’s less common these days, one still finds recipes to make, for instance, homemade gin from store-bought vodka.

From an unknown 19th century distiller, here’s

The manuscript goes on to calculate that the profit on 100 gallons of apple whiskey converted to gin is $16.30, or about $225 in today’s money. Not enormous profit, but if it were steady, one eventually could buy a house.

Me? I think it would be a shame to strip the apples from apple brandy, especially when so many good ones are coming back on the market. If you're curious about American non-grape brandies and happen to be in New Orleans next month, check out Paul Clarke's session Fruit of the Still at Tales of the Cocktail.

From an unknown 19th century distiller, here’s

To make gin out of apple whiskey

Fill hogshead of 100 or 120 gs. [gallons] with apple whiskey, into which pour a bushel of charcoal—stir the charcoal every hour for two days—stirring so often may not be necessary—then draw off whiskey and put it in a still—distill it and it will be found perfectly clear of the apple—In this state if mixed with French brandy, jamaica spirit or holland gin in the proportion of about one third whiskey to 2/3 of foreign liquors it will impart to the liquor any unusual taste or flavor.

If in the distillation you add 15 or 20 lbs of juniper berries to the hogshead, it will make good gin.

Before the still is filled 15 or 20 gallons of Water must be put in the still.

A 60 gallon still may be run out twice in the day—Charcoal must be made out of maple, chestnut or light wood—must never be wet—When taken out of the coal pit they should be put out by throwing dirt over it—burnt perfectly well—out at the top so as to let the smoke out—to be ground fine.

The manuscript goes on to calculate that the profit on 100 gallons of apple whiskey converted to gin is $16.30, or about $225 in today’s money. Not enormous profit, but if it were steady, one eventually could buy a house.

Me? I think it would be a shame to strip the apples from apple brandy, especially when so many good ones are coming back on the market. If you're curious about American non-grape brandies and happen to be in New Orleans next month, check out Paul Clarke's session Fruit of the Still at Tales of the Cocktail.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Cthulhu Tiki Mug

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn.

~ Cole Porter

A casual look around the Whiskey Forge reveals that we are modest in our affection for neither liquor nor books. Even the barely interested can see that whiskey and cookbooks practically bow our shelves. The slightly more curious may note that there's an awful lot of rum as well...and swizzle sticks...and there, in the corner, a small case of tiki mugs. Downright nosy sumbitches will realize that someone, at some point, acquired an inordinate amount of materials by and about the American weird fiction writer, HP Lovecraft.

That would be me.

|

| Horror in Clay prototype |

My days of actively prowling for Lovecraft books and ephemera are behind me. The hunt was far more enjoyable before the coming of the internet. Every book, pamphlet, or document I uncovered in a Pennsylvania barn or a Kansas City estate sale seemed like a little gem, like some real accomplishment. "I found this," I would think, "because I am very good at what I do and know the market better than these people." Now? Eh. Now when I want a title, I search online auction and antiquarian book sites in North America, Germany, Belgium, France, the Netherlands and — with a flurry of keystrokes — have the thing in my hands in no time at all. Effective? Sure. Fun? Not really.

But I do still leave room for serendipitous discoveries. And sometimes they come by way of that same internet that's sucked so much joy out of book hunting.

Jonathan Chaffin's campaign on Kickstarter brought a smile to my face and made me realize that I can make some room on the shelf for at least one more tiki mug. Chaffin is pimping a prototype of a mug he calls The Horror in Clay. It's taken from a line in Lovecraft's 1928 story The Call of Cthulhu about the dreams of artists and madmen the world over whose febrile nightmares are stirred by Cthulhu, a giant tentacled and winged entity who slumbered fitfully in the sunken South Pacific city R'lyeh. At least, it slumbered at the beginning of the tale...

Chaffin is looking for various levels of contributions to his funding campaign to make a full run of several hundred mugs. Tiki folks will go for it. Lovecraft geeks will want in on the ground floor. The level I'm interested in starts at $40. For that, contributors get a finished 28-ounce mug. Mo' money, mo' mugs.

This leaves me with two questions: (1) When will they be cool enough to handle? and (2) What would Cthulhu drink?

Goes well with:

- Jonathan Chaffin's Horror in Clay campaign is here.

- My review of Jay Strongman's book (with an intro by Tiki Farm's Holden Westland) Tiki Mugs: Cult Artifacts of Polynesian Pop

- We've covered Lovecraft here at the Forge before. There's both the candied Cthulhu-head citron I made last November as well as a short film based on HPL's 1926 story of horror in the Cool Air.

- Lovecraft's not the only oddball writer whose stuff I snagged at every turn. Of a once-huge collection of Charles Bukowski materials, one of the few remaining items is a goof, a counterfeit, a sheet of fake stamps that would fit right in Thomas Pynchon's Crying of Lot 49.

- My Culinary Library: What Good Does It Do? I've spent the better part of three decades collecting books on food and drink. Why? What good could possibly come of it? Here are some thoughts on the value of such a collection.

- Finally, if you believe that's a Cole Porter quote, I've got a mug I want to sell you for $80.

Monday, June 4, 2012

Bookshelf: John Egerton's Southern Food

In the summer of 2004, I threw a small get-together in Birmingham, Alabama. I was on the board of the Southern Foodways Alliance then, a group dedicated, in a nutshell, to celebrating the food and drink of the changing American South and the people who made it. Maybe a hundred of us were there for a small conference. After two long bus rides that day, the group was beat, so I invited a handful to come up to my hotel suite for restorative drinks and food once they'd recovered from the sun, the bourbon, and the rides.

One of those was historian John Egerton.

A few restaurateurs showed up. Several editors from papers, magazines, and broadcast news were there. Bartenders and writers rounded out the group. A half-dozen different conversations rose and fell until one voice—one kindly, avuncular voice—dominated the room: Egerton's.

Egerton is a charmer with a ready smile and (almost) always a kind word to say. He so mesmerized this group of experts with his tales that they soon gathered around him in a loose semicircle on the floor and spilled onto beds and chairs, absorbing warmth from the Promethean fire of his insight and wisdom.

John Egerton is a central figure in the modern history of Southern food and the man can tell a story like nobody else. He was one of the architects of what became the Southern Foodways Alliance around the turn of the millennium. His 1987 opus Southern Food has never been out of print and it remains the only book of which I own two copies — one for the shelf in the library and a reading copy for the kitchen, a copy I don't mind getting splattered or dogeared. I buy secondhand copies when I come across them to give to friends. Though it has recipes — and plenty of them — the 400-page book is as much travelogue and history as it is a cookbook.

This morning, I learned I'm not the only one who acts as a nano Southern Food distributor. In The Oxford American, Rien Fertel reflects on the 25th anniversary of the book's publication and how, as a post-Katrina New Orleanian, it held special resonance. He writes:

Goes well with:

In his essay, Fertel laments only a single chapter in Egerton's book on New Orleans. If you, too, want more on that city, see these two:

One of those was historian John Egerton.

A few restaurateurs showed up. Several editors from papers, magazines, and broadcast news were there. Bartenders and writers rounded out the group. A half-dozen different conversations rose and fell until one voice—one kindly, avuncular voice—dominated the room: Egerton's.

Egerton is a charmer with a ready smile and (almost) always a kind word to say. He so mesmerized this group of experts with his tales that they soon gathered around him in a loose semicircle on the floor and spilled onto beds and chairs, absorbing warmth from the Promethean fire of his insight and wisdom.

John Egerton is a central figure in the modern history of Southern food and the man can tell a story like nobody else. He was one of the architects of what became the Southern Foodways Alliance around the turn of the millennium. His 1987 opus Southern Food has never been out of print and it remains the only book of which I own two copies — one for the shelf in the library and a reading copy for the kitchen, a copy I don't mind getting splattered or dogeared. I buy secondhand copies when I come across them to give to friends. Though it has recipes — and plenty of them — the 400-page book is as much travelogue and history as it is a cookbook.

This morning, I learned I'm not the only one who acts as a nano Southern Food distributor. In The Oxford American, Rien Fertel reflects on the 25th anniversary of the book's publication and how, as a post-Katrina New Orleanian, it held special resonance. He writes:

His thesis stung hard. It resonated in that place that wished this physical and emotional inundation that accompanied Hurricane Katrina was all a very bad dream. The South’s “past now belongs to myth and memory,” he wrote, while its food endured despite the intrusion of that decade’s new American cuisine and its “sin of subtraction.” Modern cookbooks removed fat, salt, and sugar from recipes—cooking no longer took time. Egerton highlighted the endangered species, those Southern foods struggling to survive: country ham and crawfish bisque, Brunswick stew and slow-cooked pit barbecue. The region’s diverse culinary cultures, like my flooded city, required defenders and preservationists.Read the rest of Fertel's essay here. And if you should relocate to New Orleans and run into Mr. Fertel, he may just set you up with your own copy of Southern Food. Maybe you could trade some whiskey or barbecue...

Goes well with:

In his essay, Fertel laments only a single chapter in Egerton's book on New Orleans. If you, too, want more on that city, see these two:

- John Besh's cookbook My New Orleans written after Katrina: "The story of our city is greater than those storms. We have been here for over 300 years, and we'll be here for another 300."

- Sara Roahen's Gumbo Tales: Finding My Place at the New Orleans Table. A book I've given away so often I no longer own a copy for myself.